Sporting organisations have role to play in disaster recovery

In this Caribbean of ours, we often find ourselves as a nation, all twisted up whenever disaster strikes. Politicians tend to seize the opportunity to grab the headlines as often as possible, with a crude mix of suggested empathy, sometimes shedding a ‘political tear’, and outright exploitation of the chance to access much-needed resources, much of which often appear to be distributed along politically partisan lines, regardless of the suffering of others.

In life, we are often forced to acknowledge that disasters lead and leave many suffering to the point of hopelessness. However, many fail to consistently apply their critical thinking skills to analysing what actually happens in St Vincent and the Grenadines, in terms of human behaviour, when disaster strikes. Over the past several years we have had much experience in this regard.

Our leaders are quick to claim that we are a resilient people. Indeed, we are. There is evidence of this in the apparent acceptance of what passes as benevolence from our leaders and the fact that when the dust settles, few of the affected are better off than they were prior to the occurrence of the disaster.

Hurricane Beryl 2024

We have recently experienced the disaster spawned by the passage of Hurricane Beryl. Much of St Vincent and the Grenadines have been affected. However, there is unquestionable evidence that the Grenadines experienced the worst damage. Indeed, in Canouan, Mayreau and Union, the extensive nature of the damage could only lead to the situation being described as a major disaster.

Over the next several weeks, much will be told of the truth about the damage and the real cost in terms of loss of lives, loss of possessions and the destruction of infrastructure. We will learn too of the potential cost of the recovery and rehabilitation efforts needed to facilitate life on these islands.

Those of us who have been spared the destruction evident in the Grenadine islands will never truly comprehend what it had done to the people who have populated them all their lives. We have no true capacity to ever be able to say, “I know how it feels’, and should make every effort to resist any temptation to utter those words. It is only those who experienced it that can attest to the impact in its totality, not the least important of which must be the mental trauma with which they now have to live for the rest of their lives.

There is enough blame to share around in respect of this nation’s insistence on strict adherence to the building codes, over the years. Indeed, some years ago it was asked whether or not we had made adaptations or modifications to the country’s building codes since those that were established following the passage of Hurricane Janet in 1955. History reveals our near ineptitude in the area of maintenance of those structures that we have built.

The nation’s most affected people are struggling to come to terms with what they have just experienced and are attempting to put their lives together, without being able to escape the potential option of mendicancy, a phenomenon known only too well by countless peoples across the world.

Beryl has left us in a state of flux; one that is all too common for small, developing nations where politicians engage more in chest-thumping as they traverse the world in pursuit of assistance that they need to facilitate repair and recovery. The option is about playing the politics and the people of the Grenadines are all too familiar with this. It is as if it is in their DNA, so often has it been their experience.

There is a tendency for people to be dehumanised in the process of ‘official recovery’ because of the way they are treated in the circumstances. We often forget that they are human beings imbued with a sense of dignity. It is hard enough when they have lost all that they would have owned, far worse when they are being compelled to also lose their dignity. They have nothing left.

Sport and people development

Decades ago, we found our leaders being ignorant of the valuable role that cricket played in the Independence movement across the Caribbean, led by cricketers who were plying their trade in England.

Despite having gained Independence with immeasurable support by cricket and its Caribbean players, successive generations of our region’s leaders continue to cite sporting successes only. The broader picture is anathema.

We have long been taught that development is about people. Walter Rodney in his epic work, ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’, chronicled the systematic economic and other forms of rape of Africa by Europeans to facilitate European development and bolster their continued expansionism. This latter objective was also facilitated by the use of sport as a panacea, a means of distracting the local populace from their ambitions to take control of their lives and societies. Yet the same colonisers used sport as part of their development ethos at home, even if that meant denying ‘freed’ people, first, their right to participate and secondly, their proven excellence on and off the field of play.

We live in a country today that lacks the basis for a genuine sport culture. Successive governments have continued to see sport as frivolity and govern the nation guided by such a disturbing understanding.

Our education system has historically imposed on successive generations an approach to life that belittles physical activity and sport. It is the reason we cannot yet boast of having inculcated a national sport culture.

Through our history, politicians have continued to underplay the importance of sport to the human condition, aping the cruel legacies of colonisation while mouthing epithets of how much we have advanced, a startling contradiction that remains integral to our political culture.

In our country, we have always found ways of delivering platitudes of the successes of sportspeople without due consideration to their contribution to our people.

The response of those in authority to sporting success is the conferring of ambassadorial status complete with the diplomatic passport. No attention is paid to such individuals unless they have, at the same time, distinguished themselves academically. In such cases, it is the academic achievement that is highlighted, and commendations go for having struck ‘the right balance’ on one’s pursuit of a career.

It is unfortunate that around the world generations of sportspeople have been able to emerge as leaders of immense importance in some societies that allow for excellence in sport to be duly recognised and rewarded. That is not the case here. But we ought not be surprised by what obtains before our eyes.

It is something of a grand tragedy that even as we witness the increasing number of Caribbean athletes who have climbed to the top tier of international sport, the region’s leaders consistently fail to acknowledge the virtues of sport. We ignore the capacity of sporting endeavour to help in the healing process in society. Instead, we shy away from it, downplaying the Mandela experience with rugby in South Africa during. His tenure as that nation’s President following decades in prison on Robbin Island.

Sport can help the healing process, but it must be given the chance to do so without allowing itself to become mired in the political myopia, cynicism and downright victimisation. Political patronage has no room for sport.

Sport can heal the pain of Beryl

The religious leaders around St Vincent and the. Grenadines have found their voices in the aftermath of the passage of hurricane Beryl. This we ought to have expected. What is important is for them to engage in critical self-analysis and respond to the concerns of Vincentians in respect of why they do not have voices for the voiceless all of the time. That is supposed to be their mandate, their mission.

Sport allows people the opportunity to experience and enjoy freedom. It allows people to be authentically themselves, unvarnished.

Sport opens up avenues for self-expression without fear of recrimination.

Sports allows people to be.

Sport brings people together.

In the aftermath of hurricane Beryl, sporting organisations can and ought to come together to help people recover their dignity and their right to be.

Bishop Desmond Tutu once declared, ‘I am what I am because of who we all are’. The statement is simple but decidedly profound. Sport epitomises this fundamental truth.

The sociological reality is that sport has the propensity to bring out the best in us because we are truly free to be when engaged on the field of play.

Our national sporting organisations can do for the peoples of the Grenadines what no politician can ever do for them, grant them emotional relief.

I am appealing to our sporting organisations to rouse from their slumber and offer the peoples of the Grenadines opportunities to be genuinely free and to resolve to remain that way for all time.

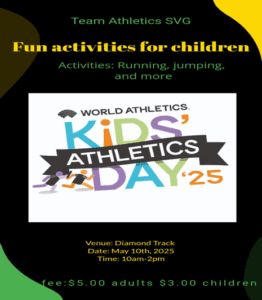

In this vacation period, the children of the Grenadines can be treated to play as a means, not of merely occupying themselves, but building resolve to be whole persons, capable of keeping their heads high because of their firm conviction that they can overcome adversities like hurricane Beryl.

The people of the Grenadines already know adversity. It is in every aspect of their lives. I appeal to sporting organisations to help the healing process, not with sadness but with dignified support that allows the people to smile and give thanks for being alive, knowing that because of it they can do better for themselves.

Perhaps the time has really come for Vincentians to unite to build a better society. Not one that is dictated by the leader’s political ethos but rather, by the people themselves, filled with their life experiences and unyielding commitment to be all that they can be.